When it comes to writing the other, what questions are we not asking?

Save this article to read it later.

Find this story in your accountsSaved for Latersection.

Do you have any advice for writing about people who do not look like you?

I was at the Bread Loaf Writers Conference this summer, on a panel of writers of color.

Jericho Brown, Ingrid Rojas Contreras, Lauren Francis-Sharma, and I took questions from Cathy Linh Che.

It was a good conversation.

I realized I had been waiting for it.

Dreading it a little.

Online, it has become one of those fights with no seeming end.

They dont want an answer; they want permission.

Which is why all that excellent writing advice has failed to stop the question thus far.

I dont answer with writing advice anymore.

Instead, I answer with three questions.

Why do you want to write from this characters point of view?

But for most of us, the stories we hear are the first stories that teach us.

Stories in the news.

Stories were taught at school.

Gossip, trash talk, and jokes, which are the shortest, complete form of narrative.

How you grew up, who you grew up with, how you know them.

Modern fiction works differently.

I knew the questions this student still had to answer because I knew people from this community.

I had to draw her attention to everything she didnt know.

She seemed resentful throughout.

Her previous adviser had believed she could write this novel, too.

Do you read writers from this community currently?

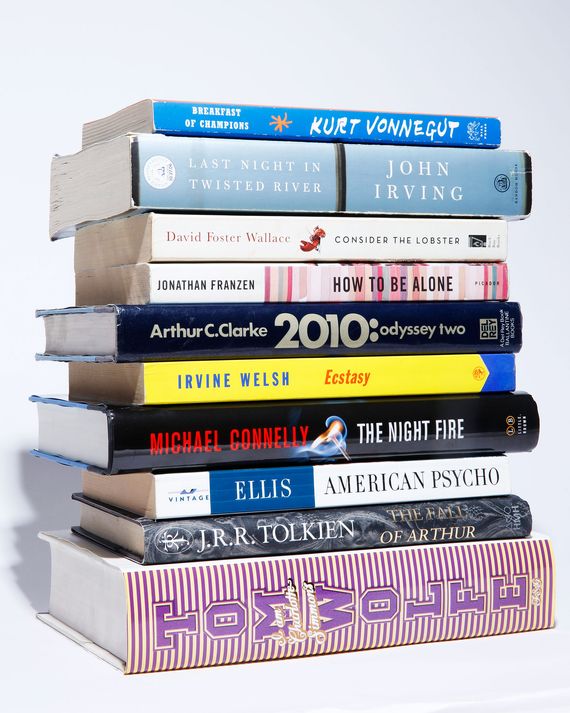

People dont often know their blind spots until they do a simple audit of their bookshelf.

Most of what has survived to us thus far is literature written by white male writers.

But most of us writing now were not educated by that expanded canon.

I teach roughly seven writing workshops a year, and have since 1996.

In general, the beginner fiction that writers produce is what they think a storylooks like.

Those stories are often not really stories they are ways of performing their relationship to power.

They are stories that let them feel connected to the dominant culture.

Or my own first stories, when I did much the same as these students.

In the 1980s, I had to learn how to write myself and people like me onto the page.

My own life on the page felt impossible to explain in any detail when I was a student writer.

Why do you want to tell this story?

I think every writer needs to ask themselves this question.

But the urgency of it takes on a different shape when we think about other cultures.

They were both white.

The woman was more social, intent on drawing me out.

Do you believe writing can be taught?

I said I did, unlike some writing teachers.

He told me about his desire to write mystery novels.

He was a retired police detective.

He has spent a career solving crimes he cant talk about.

But there were questions.Does this have to be set in London?

I was interested in the crisis a retirement can be within a long marriage.

I was also interested in writing a thriller.

Does the story need this stereotype to exist?

If so, does the story need to exist?

A stoic whiteretiredBritish police detective and his wife did not at first glance seem like damaging stereotypes.

But even in thinking about this, I had to ask myself why I wanted to write the novel.

Other questions grew from that.

Did I really want my next novel to be set in London?

Wasnt there enough to write about in America?

What was I doing writing about a white man?

Even if I wanted to write a metamurder mystery, wasnt there some other way to do it?

These discussions distract me increasingly from the conversations Im interested in.

If Im helping students cross boundaries, I urge them to look at the ones they find within.

I also urge them to set them for themselves.

Or the inimitable Ocean VuongsOn Earth We Are Briefly Gorgeous, an autobiographical novel set in the second person.

This direct address to her Asian-American refugee to Asian-American refugee is drawn out of that history and intimate proximity.

Ituses the Japanese literary formkishotenketsu,a dramatic structure that refuses to deploy conflict.

No rising arc, no climax.

I was with him recently at NYU for a night of readings.

He said two things that night that I still think of.

What is pretentious but to have the pretense to the assumption that you belong here?

These are two polestars, a North and South.

One was what I perhaps still needed to lay down, and the other was something to pick up.

Better to catch the energy that rises when I fling myself at everything I fear writing.

Increasingly, this question is a trick question.

This game is over.

Stories they know but have never read anywhere.

Stories they always tell but never write down.

Thats what this question is really about.

If the questioner asked it of themselves more often than they asked other people.

Alexander Chee is the author ofHow to Write an Autobiographical Noveland an associate professor of creative writing at Dartmouth.