Three revolutionary works still speak to us of doubt, inspiration, and grace.

Save this article to read it later.

Find this story in your accountsSaved for Latersection.

Even then, everyone knew something shocking had happened.

Painters were looking upon his works as miracles, it was written.

Rivals groused that this monster of genius had wrought the end of painting.

(I adore Mannerism for all of this.)

All this is why Caravaggios follower Nicolas Poussin praised him for coming into the world to destroy painting.

Caravaggio would be dead within ten years, but he changed art history.

He may have been murdered himself while trying to get back.

A lot rode on this commission; plus, the pope might even see it.

The cycle was painted in a tear he must have been on fire.

The last painting of the story was begun first,The Martyrdom of Saint Matthew.

He has murdered the old man, running his heart through with the now-withdrawn sword.

Blood spurts from the mortal wound.

That man is Matthew; this is his martyrdom; he is already dying.

The slayer stands in dominion over Matthew the way Muhammad Ali stood over a knocked-out Sonny Liston.

We are stunned, hypnotized, repelled, frightened, fascinated, confused, and stupefied by it all.

Caravaggios realism is so derived from observation that the scene becomes undeniable.

According to some tellings, Matthew was martyred in Ethiopia after saying Mass.

This is why he wears vestments here and seems to be on the steps of an altar.

People in various states of nakedness suggest baptisms.

Predator and prey form this riveting, still center of the pandemonium around them.

The geometry is a kind of swirling, chambered-nautilus spiral.

Our eyes search for anything anchored some place of stability among the chaos.

An altar boy in white robes screams and flees.

His right arm mimics Matthews; his trunk turns the opposite way of the murderers.

Caravaggio often echoes, opposes, mirrors, and flip-flops poses.

Often someone will face forward next to a figure facing away.

As maximal as theMartyrdomis, theCalling of St. Matthewis minimal.

This is the scene where Christ calls Matthew as his disciple.

The entire top of this picture is almost empty.

Whole areas are just blackness.

In a dim room, five figures sit around a table.

We know Matthew was a Jewish tax collector.

Note his elegant belt.

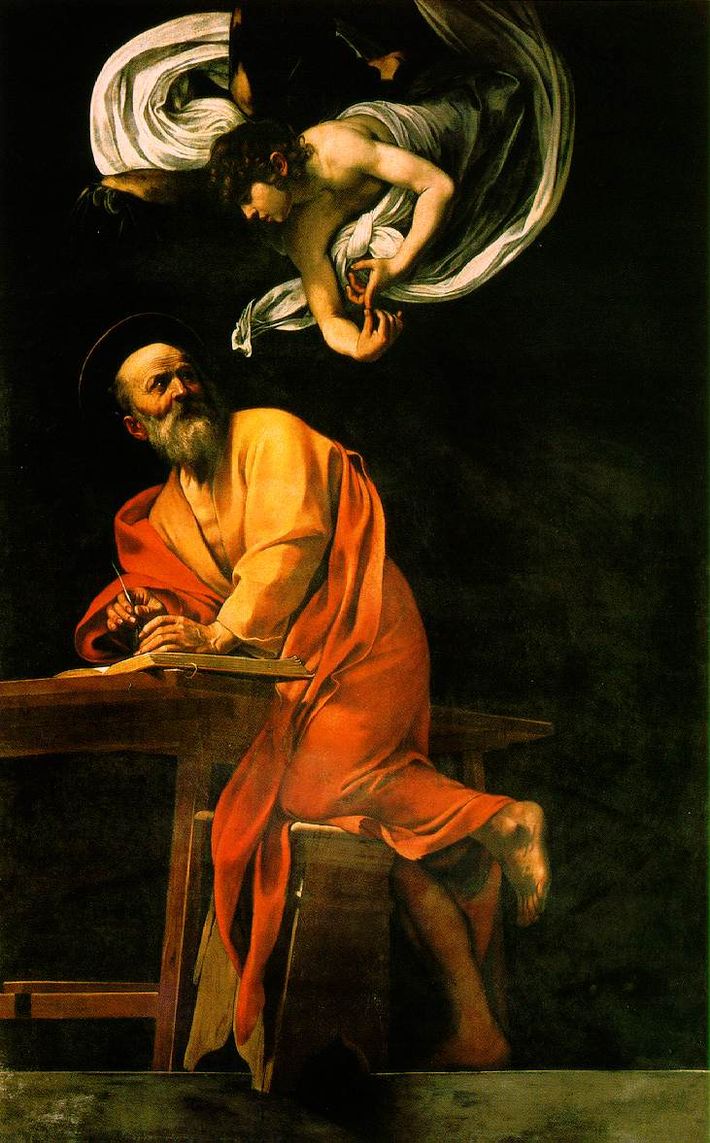

The final painting in the cycle, theInspiration of St. Matthew,is Matthew writing his Gospel.

Hes so taken by something that he hasnt even sat down and turns on one knee while standing.

(The stool is about to fall off the ledge its on.)

Ive never seen anyone painted this way before or since.

I know this pose in my bones, though.

Ive run to my desk in the grip of imagined inspiration like this, possessed.

Matthew isnt looking at the page.

It is patient angelic aid for an author trying to get this right.

Ive seen these paintings thrice; each time ranks among the best days of my life.

A mystery of some kind beckons; a skeleton key that wants turning.

This way of rising speaks volumes.

But what is it telling us?

Then, bam, after ten days, I see it.

Amid all the action, observation, and dramatics, a paradoxical deep content opens.

This is a slowness and desperation that all writers and artists know.

Matthews hand doesnt extend in protest or terror.

It extends in a gradual, final acceptance of grace, of knowing something new.

In these frozen moments of painting, time eases into some cosmic soup of slow knowing.

This lets me finally let go, too.

I give up on knowing how Caravaggio created this quelling quietude of balm within clamorous space.

Instead, I just savor it.